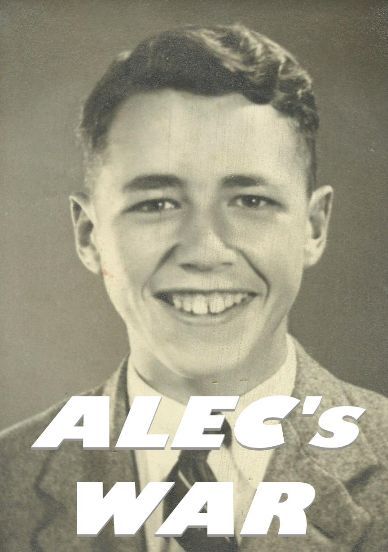

This is the story of the wartime experiences of Alec Ramage, told in his own words

Edited by Andrew Ramage

With thanks to Benjamin Harrison-McGill

Copyright Andrew Ramage 2021

Website Ian Ramage, copyright 2022

Early Days in Beckenham

Woodbrook School in Beckenham was a school based in a large Victorian house in Hayne Road on the corner with Blakeney Road. It was listed as a school for girls and young boys, and from about 1933 at the age of five I was one of the young boys. I remember very little of this period except that the school was well run by Miss Gladys Mead with Miss Vida Elrin assisting her. Woodbrook School in fact, flourished for many years and eventually closed in 1960.

The house was subsequently demolished and a modern single storey building erected. A new school was opened for handicapped children, and the name of Woodbrook was retained.

As a young boy I lived with my parents at 41 Barnmead Road. Some time later we moved to Kingshall Road for a short spell, near Kent House Station, to a house backing on to the railway with steam trains passing regularly to and from the Kent coast on the embankment at the end of the garden.

After this, a move was made to 11 Brackley Road, a large Victorian house converted into three flats, basement, ground floor and the upper flat on the two floors above. We lived in the ground floor. Brackley Road was a wide unmade road, lined with large trees and was on the large well known Carter Estate. The name was from John Carter, a rich timber merchant who came to Beckenham in 1773 and acquired large areas of farmland. He died in 1806 and was succeeded by his nephew. The Estate spread from Shortlands to Crystal Palace with a total of about nine miles of unmade roads to dampen the dust which was often thrown up as cars passed.

At the top of Brackley Road was the Abbey School, a well-known boys school in Beckenham, which I went to when I was about eight years old. The headmaster was Robert T. Gladstone, a popular figure, who was a Grand-nephew of the famous Victorian Prime Minister. The school was built in 1868 by the Reverend Thomas Lloyd Phillips on what was then Copers Cope Farm, and the architecture of the school was built to give the impression of a venerable antique Abbey building. The school stood in very spacious grounds liberally adorned with trees, and was bounded on three sides by Brackley Road, Southend Road and Park Road. The main teaching building was diagonally across the corner of Brackley and Southend Roads and there was an archway over the one road which ran through the grounds, connecting the main building with the other buildings containing the dining room and dormitories on the Park Road side.

One road entrance was about fifty yards down Brackley Road, where it is to-day, and after meandering through the grounds we went through to the

other gateway at the corner of Southend Road and Park Road. The original Gateway at this point is still there today.

On the Park Road side of the school was a large playing field area, and the school also had a large sports field situated on the other side of Brackley Road, in an area bounded on three sides by Brackley Road, Worsley Bridge Road and Stumps Lane, with a small roller-skating rink which was well used. I had good reason to remember the playground, for at some stage while playing there, I fell heavily and broke two bones in my left wrist. After a hospital visit and X-ray, I was in plaster for some days.

The spacious grounds were well-used for pageants and displays, and one such display which I can still recall clearly was one summer sports day, when I took part in a large physical training display, watched by parents and friends from the grass banking overlooking the playing field area.

At one end of the grounds was a hedge with a central opening on to the field, and we formed up out of sight behind the hedge. We were all attired in P.T. kit and carried a white baton about two feet long. At a given signal we all marched out on to the field, carrying our batons horizontally, singing as we marched the “British Grenadiers”the first lines of which ran:- “Some talk of Alexander, and some of Hercules, of Hector and Lysander, and such great names as these”.

We marched the length of the field and then returned in front of the assembled crowd, before forming up into a large square prior to carrying out various exercises in unison.

The master in charge was Maurice Saunders, who marched out with us and then stood in front of the display supervising the various exercises, mostly by signals and with the absolute minimum of verbal command. I am sure the display must have been very impressive, and when it was over the procedure was reversed as we formed up again and marched off the field. This time as we marched we sang ‘’Marching through Georgia.’’

In the far corner of this ground, next to Park Road at the furthest point from the main road, there was an open-air swimming pool which we all enjoyed using. It was built largely from contributions from parents and friends but sadly was not in use very long as it was only completed a year or two before the war.

I have always enjoyed cycling. I often went with my Mother and one day, probably in 1938,we were cycling along Manor Way when we stopped at the short path between two houses which led up to Elgood playing fields (today Kelsey Park School is built on this site.) There was a soldier standing guard at the entrance, and looking up the path there was the unmistakable sight of a gun emplacement. Somewhat surprised my mother asked why there should be an anti-aircraft gun there and the reply was very definite, to the effect that it would very soon be needed. This was the first inkling I had, at the age of ten that war was not too far away.

When war was declared on 3rd September 1939, I was on holiday with other members of the family at my Grandfather’s house at Kingsgate, near Broadstairs on the Kent coast. We all listened to the 11-15 a.m. broadcast by Neville Chamberlain on that sunny Sunday in the open hall at the foot of the stairs in the house. He had hardly finished when we heard the first wail of an air raid siren which was such a common sound later. This warning was apparently caused by an unidentified aircraft crossing the coast, and the ‘all clear’ soon sounded.

In Margate that afternoon there was great calm but the first signs of war were appearing. Important buildings were being sandbagged and posters about the black-out and sirens were appearing.

Preparations for War

My holiday didn’t last much longer and I soon returned home to Beckenham. The general schemes of evacuation were beginning. The Abbey School moved to Woolacombe on the North Devon Coast and I went with it. Woolacombe is a village standing at the northern end of the three mile Woolacombe sands, surrounded by rolling hills. A great deal of this coastal area was owned by the National Trust. Out to sea in the distance stood Lyndry Island.

Woolacombe was about 235 miles from London by train and it was a long and slow journey, taking the best part of a day to get there. The steam train went to Exeter and then trundled on to Barnstaple and eventually reached Mortehoe station, the nearest rail station to Woolacombe. A two mile car ride took us to Woolacombe.

The school took over four hotels in the village the largest of which was Rathleigh which was in a prominent position near the village shops and main entrance to the sands. Two of the other hotels were Hartland and Chatsworth further round the esplanade, while the fourth was Devonia on the opposite side of the road to Rathleigh, and was used solely for teaching where we assembled each day.

With the evacuation the school left behind many boys and a few masters, but another school from Beckenham, Clare House joined us and helped to make up the numbers.

I stayed in Rathleigh Hotel, which was run by Gordon Storrs, a master who had come down from Beckenham, a popular, well-liked and cheerful person, who was nearly always to be seen wearing plus fours, a fashion generally more commonly associated with golfers.

It was certainly a contrast to Beckenham to be in the picturesque countryside by the sea, but all was not complete tranquillity, as while we were there army tanks arrived in considerable numbers for training purposes. The tanks used the sands going up and down the three mile length for many hours at a time. They were parked at the side of the village in what is now a coach park, and went straight from there to the beach.

Coincidences in life often come in quite a surprising way and one such occurred while I was at Woolacombe. On Sundays the soldiers of the tank regiment on church parade would march up the main hill to the small parish church about half a mile distant. We often used to watch them and one day I spotted my Uncle Jim amongst them, and neither of us knew the other was there. We met up several times later before we went our separate ways. The training had a very serious purpose as many of the tank crews were later engaged in the desert fighting in North Africa.

Gordon Storrs was very keen in ensuring that we learned as much as possible of the environment and he took us for many walks around the district to explore the countryside. Some of these walks took us along the beach where we had another reminder of the war. We would find green glass balls about two feet in diameter, which had been washed up and left high and dry on the sands. We later learned that these were used for holding up anti-submarine nets guarding the Bristol Channel, and they had broken away.

The school did not stay very long in Woolacombe, as it found the line of communication from London was too far stretched, so a decision was made to move to East Grinstead in Sussex – just as the Battle of Britain was about to start!

Before arriving at East Grinstead I spent a short school holiday in Beckenham. France had just fallen to the Germans and we were told to expect anything. The most noticeable feature was the appearance of barrage balloons. We were on the edge of the barrage and the last balloon was situated in a field in front of our house.

Air raid shelters were to be seen everywhere. We had an Anderson shelter in our back garden, and street brick shelters were appearing, to be used if caught out in an air raid.

We had a gun battery built near us and at night searchlights probed the darkness in practice for the real thing.

East Grinstead was about thirty miles from London and about half-way between London and the South Coast. The school itself, still joined by boys from Clare House, had taken over a large mansion which was once owned by Sir Abe Bailey, the South African millionaire. It was situated on a high hill in a thickly wooded area overlooking the village of Forest Row. A large playing field was on the side and the ground went down steeply to a swimming bath at the bottom. Sports were played and the swimming bath proved very popular – although on one or two occasions snakes were found in it!

Let Battle Commence

One of the major battles of the war, the Battle of Britain, started on 10th July 1940 when the German Air Force began their air attacks on this country. As East Grinstead was midway between London and the South Coast many of the dogfights took place in the skies above us. Little could the school have imagined when they moved from Woolacombe, that they were now going to be in the middle of a battle zone.

The initial battle raged for about three weeks when multiple attacks were made on various targets across the south and then on 15th August the multiple attacks were replaced by heavy mass raids. As young schoolboys, we were not aware of the dangers involved and found it all very exciting.

The air battles in the days ahead followed a very similar pattern. On a clear, warm and sunny summers day, first would be heard a very distant drone as the German bombers flew in at a very great height, usually well over 20,000 feet and often invisible to the naked eye. When our fighters intercepted the planes would start diving and weaving, and as they twisted and turned they could be seen now and again as tiny specks, when they were caught in the sunlight. We would hear the roar of engines, the rattle of machine gun fire, and the whining sound when planes dived. During this period we were constantly watching these fights with very little school work being done. It was very difficult to distinguish friendly from enemy aircraft, but it was a great thrill when we did see an enemy plane crashing down. Many planes crashed around us, and just after the attacks had started, I recall how frightening it was when an enemy bomber roared over the school with smoke belching from the engines, and then finally it crashed.

Two of our masters were extremely interested in all that went on, and often appeared with binoculars to give a commentary on a fight. We also saw plenty of silver parachutes slowly coming down when planes had been shot down.

One incident which we witnessed at the height of a battle was when we saw one plane dive after another. Very unfortunately one of the planes couldn’t pullout of the dive in time, and gathering speed nosedived straight into the ground. There was a loud thump as the plane hit the ground about 400 yards away. The plane turned out to be a Hurricane which had a young New Zealand pilot. Experiences like this went on for many days and we collected souvenirs from parachutes and crashed aircraft.

I returned to Beckenham for the summer holiday and it was during this time that the German losses in the battle were considerable and the daylight raids gave way to the night-time bombing of London.

Saturday 7th September saw the first of the big London raids when the docklands were set alight, and by this time the Germans had admitted the loss of air superiority. This was the start of the eight month long blitz of London with nightly bombing continuing until April 1941.

Back at school, with the end of the daylight battles, night after night we heard the distinctive beat of the bomber engines as they passed overhead on their way to London.

When we awoke about 6:30am we would still hear the roar of aircraft, but this time it was the planes on their return journey home. Many of us wondered why our large mansion, which stood out on a high hill did not seem to be a target. Out headmaster assured us that we would not be bombed, as he used to watch and said that we were the turning point for the enemy bombers, and said that the formations turned a certain angle when they reached the mansion.

This term was coming near to an end when there was one incident nearby. While we were all asleep at about five o’clock early one morning, and the enemy aircraft were returning to France, there was the loudest explosion so far and we all awoke with a start. Apparently a pair of land mines had silently floated down (by parachute) and landed in a field nearby. At the bottom of the hill from our mansion was a valley and on that morning it was covered in fog. A theory was put forward that the enemy had possibly thought that the valley was the River Medway and the mines were being dropped in a river. We visited the craters on our next walk, and they were about a mile away. They were both very large, about fifty yards apart.

Soon after this the term ended, and as Beckenham was being badly bombed, I did not return home, but went up to Glasgow, where my Father was stationed. For the holiday in Scotland, I lived with my Father in a large block of flats in a suburb in North Glasgow called Hyndland.

Glasgow had two groups of air raids lasting about a week in each case, and about four months apart. I was there for the first group. After two night raids my Father decided I must get away from the raids so I returned to London. A case of from one city under attack to another! I arrived early one morning in London after a night raid. The city was in chaos and we tried with great difficulty to get a breakfast. Buildings were burning and collapsing and fuel supplies were cut off. There were many diversions and the people looked very weary after the nightly bombing.

I spent the rest of the holidays in the country near London. The next term at East Grinstead was to be my last at the Abbey before moving on to St Pauls School.

When a large day school moves its premises the arrangements necessary to accomplish the change are of considerable magnitude but when the move is an enforced one, as in a time of war, the task at hand is fraught with added difficulties. At the outbreak of the war St Paul’s School evacuated to Berkshire at short notice and the first major requirement was that of accommodation. When agreement had been reached for the mansion at Easthampstead Park to be used for tuition purposes it then became necessary to seek living premises.

The nearby village of Crowthorne thus became the centre of Pauline living quarters at this time with many boys staying in billets. Larger houses were taken over and run as school hostels. These hostels were an experiment, and in the event one which succeeded. There was one however which was not in Crowthorne, but some six miles away in Binfield. This was “Underwood” and there was a very happy spirit which prevailed amongst those of us living, learning and playing together there during the war years.

On The Move

On a Sunday evening a considerable number of Paulines assembled at Waterloo station and made their way across the concourse to board the front part of a train for Reading. As some arrived and walked determinedly along the platform looking in the compartments for their colleagues, others already in the train were looking out. If the person outside was not considered the best of travelling companions the window blinds were quickly whisked down in the hope that he would continue past. If on the other hand his presence was more welcome shouts of recognition were made and he was almost physically hauled into the compartment. Seats were quickly taken and by the time the train departed there was usually standing room only.

The train traveled out through the western suburbs, and stops were made at Richmond and Twickenham where further groups of boys joined those already on route. The journey continued into the country and by the time Ascot was reached, where the train divided, daylight had usually faded. Black-out blinds were pulled down, leaving the compartments dimly lit by narrow shafts of light penetrating through the darkness from well-shielded lamps. Bracknell was the following station, just over an hour in journey time from London, and here the groups of boys alighted en masse making their way over the station footbridge, some to collect bicycles from storage others going through the blacked out streets to the nearest bus stops.

This was an oft repeated scene around 1941 when these journeys became commonplace at weekends and at other times when we returned to school during the war. Many of those from the train were making their way to Crowthrone, whilst there were those others of us cycling up the hill to Binfield, haversacks on back, or cases perched precariously on handle bars.

Bracknell was a compact village with a population of almost six thousand and three miles to the west, also on the main line and main London to Reading road, lay Wokingham. To the South West of Bracknell six miles away was Crowthorne. This was a rather straggling village with a population of about five thousand and in many respects an isolated place, not being served by any main road and with only a railway branch line from Wokingham. Situated almost centrally in this imaginary triangle was the mansion and grounds of Easthamstead Park. The smaller village of Binfield lies midway between Bracknell and Wokingham, just north of London Road.

In August 1939 an advance party of about eight boys had come down to Berkshire to carry out preparatory work at the mansion prior to the main force of the school following on the next month. This was an extremely industrious period for the few, who assisted in such tasks as the construction of trestle tables, cycle sheds and trenches.

In the very spacious and delightful grounds of Easthamstead Park and in close proximity to the mansion, was a small house called Home Farm where the Telling family resided. In September some Paulines moved in as well and it thus became the first of the school hostels, with Charles Hendtlass as hostel master. In six months the total number of boys there rose to twenty-five. Unfortunately, however, conditions were difficult and a number of incidents which occurred did not assist matters. Also, there was a small, but fortunately mild, epidemic of scarlet fever. Eventually a larger house, further afield in Binfield, was found and Charles Hendtlass together with his mother, who had by now come down to assist in the running of the kitchen arrangements, and the boys from Home Farm moved into Underwood which was opened early in 1940.

As the school gradually acclimatised itself to the rural scene twelve other hostels became established, all in Crowthrone and I include their names for the record. Normanhurst – Meadhurst – Ousels – Green Hedges – St. John’s Lodge –Pooks Hill –Waverley–Trevear – Whitecairn – Edgebarrow – Barracane and Larchwood.

Underwood was a rather drab grey stone building with slated roof but enhanced by its setting, standing in its own small grounds literally adorned with large trees, and a six foot brick wall afforded considerable seclusion. A short gravel path led to an unostentatious front door and this path divided two lawns at each side of the house. Earlier large scalemaps of the district referred to Underwood as a cottage and there was evidence that extensions had been added at a later date. At one side of the house there were flower beds dividing the front lawn from the back garden, and on the other the lawn was bounded by a driveway from the side gate which led to the double garage and other small outbuildings. Behind these was a considerable back garden, well laid out, with a large part devoted to fruit and vegetables.

Inside the house Charles Hendtlass had the central front room as a study and living room. On one side of this were two rooms known as the inner and outer studies, and on the other was the dining room. The kitchen quarters lay at the back, while upstairs there were five main bedrooms, known as the prefects room, the big bedroom, the little room, the end bedroom and the attic. It can be said that the hostel was adequately, if perhaps sparsely, furnished.

This briefly was Underwood when twenty six boys took residence in 1940. By 1945 fifty eight of us were to have passed through its doors, some perhaps staying only for a term or two, others for nearly the full period.

Helping Hands

As we were to have three meals a day at Underwood, returning daily from school for lunch, it was obvious that one of the first requirements would be the smooth running of meal arrangements.

Whilst Mrs Hendtlass, virtually unaided, did sterling work with meal preparation, there were table and other arrangements to be organised which needed our full participation. So it was that an orderly system was devised which involved the carrying of plates and food between the kitchen and dining room, with the added tasks of washing up after the tea meal and cleaning up generally.

For various reasons it was difficult to establish a system that did not have one or two shortcomings, and over the years a number of different schemes were tried. A difficulty which kept recurring was absence either through illness or unavoidable lateness from school or Crowthorne. One of the first systems which was devised split the hostel into two teams, each of which operated for a week in turn. Inside the team two of us might have been responsible for the breakfast and lunch meals, and four for tea when washing up was also involved. As an incentive, and to instill keenness, Mrs Hendtlass would offer a small prize from time to time to the best team. This worked well for some time but eventually came in for criticism and a number of other ideas were then tried, until another definite plan was adopted and generally accepted as being the best. Two of us would be responsible for all meals for one day, and then had a completely clear period until our turn came round again.

Careful as we were handling a considerable amount of crockery, there were mishaps at times, and to meet these we usually paid one shilling at the beginning of each term towards the breakage bill.

One or two of us did other work apart from the orderly team, so to speak, and became associated with specialist tasks. For instance there was the laying of tables before meals and this was the concern of John Price, Jerrold Weinstein, Peter Norman and John Corcoran over the years. The making of toast for breakfast most mornings was carried out by Eddie Veronique who did this admirably for most of our stay, and was aptly presented with a toasting fork when he left. Peter McCormack continued this for the final terms.

So it was that we all made our contribution towards the provision of our daily bread, but there were a number of menial tasks which we performed from time to time, to affect the smooth running of the hostel. For a time there was a qualified gardener, but eventually he had to give up the work and so a number of us were required to allocate one hour per week in the evening, for digging, weeding or the delights of fruit picking. Wood chopping was another job requiring our aid in the winter. Necessary and many were the jobs we performed, but relatively few were the difficulties and a happy rhythm was usually achieved.

A small and distinctive sounding hand bell was rung to summon those who were orderlies, and then about ten minutes later, a second ringing announced to all that the meal was served and ready. There were still however a number of occasions when the first bell was rung with no apparent response, and after a short interval a voice was heard shouting just one word down the passage – “orderlee!”

"On The Lawn"

As might be imagined, spirits were high at the end of terms but good natured boisterousness and restlessness were not limited to these occasions – this would be too much to expect! From time to time various pranks and diversions were witnessed. Naturally enough this prompted Charles Hendtlass to speak on such matters and pronounce that all rowdiness would be prohibited indoors, if only for the reason that things were easily broken. If there were surplus energies to be used up they were to be expended on the lawn outside. So it was, when any robust activity appeared to be brewing, the parties concerned would stop and echo the words ‘on the lawn’ which became a catch-phrase in this context for quite a time.

The main lawn was the scene of many of our activities, the most popular of which was football, which was played at all odd moments. Two or three would start playing and others joined, until a game was in progress. The size of the lawn curtailed the game to some extent, but this was compensated for by earnest endeavour and verve.

Our continued playing led to the desire for friendly games with outside teams, and a number of matches were eventually arranged. One of the first of these, and certainly to be remembered by all participants, was played against a team of young people representing the village of Binfield, on a field a short distance from the hostel. It was perhaps unfortunate that the game in question was not exactly a friendly match, in the sense that the village team were bursting with earnestness, vigour and enthusiasm, at the expense of any apparent soccer craft. Leo Melzer, Jerrold Weinstein, Peter Willis and Billie Keene were four who played, and by the end of the game most of our team were nursing their injuries! Nevertheless the proceedings ended on a happier note when the village team were entertained to a sumptuous tea at the hostel, prepared so expertly and characteristically by Mrs Hendtlass.

The fixing of times convenient to all, and the distances involved, in many cases prevented a number of matches from being played, and a number were arranged on paper only to be cancelled for these reasons or due to illness. One such match arranged was against the combined hostels of Waverley and Trevear. This was played in Crowthorne and resulted in a draw, two goals each. For the record our team in this game comprised John Dunwoody in goal, with John Singleton, Norman Kirke, John Claridge, John Garcia, John Pierce, Roger Batey, Adolfo and Manny Buylla, Monty Foster and Peter McCormack. Another game played there against the school hostel was won by us two goals to nil. The team being Maurice Swaine in goal, John Pierce, John Singleton, John Claridge, Monty Foster, Bryan Cross, Dennis Gorde, John Dunwoody, Adolfo and Manny Buylla and Dennis Marks. A further match was arranged against the Broadmoor Asylum from Crowthorne but it was never played as our team found the game cancelled on arrival at their ground at Easthampsted Park; their team did not put in an appearance!

Compared with football, cricket only came as a very poor second in popularity on the lawn, no doubt due to fact that the ball was frequently hit for a six – over the wall! Nevertheless I have a note that at least one outside match was played, against a team representing the village of Binfield, and although we lost it was far from the debacle that the soccer match proved. In fact we scored twenty eight runs against their thirty two. Our team who played were Marty Foster, John Singleton, John Claridge, John Pierce, John Dunwoody, Peter Crook, John Krieger, Peter McCormack, Maurice Swaine, Peter Broad and Adolpho Buylla.

Although table tennis is essentially an indoor game, and the table in the outer study was very popular, it was played on the lawn on occasions in fine weather. And I am therefore taking this opportunity to include it here. We were in fact able to arrange at least one match, against Edgebarrow in Crowthrone, which we lost two games to five, John Dunwoody and Norman Kirke being the only two of our team to win their matches.

Leaving aside the popular spats, there was one other activity which gave plenty of fun while it lasted,and which can be called human pyramids. The idea was for a number of people to stand in a circle and with arms linked, with a similar circle of people mounted on their shoulders, and with at least one person - I recall Norman Kirke on many occasions – triumphantly on top.

The lawn thus became the focal point of many outside recreational activities, but it did have a few quieter moments on hot summer days when tables and chairs were brought out, complete with refreshing drinks.

In the corner of the lawn opposite the house was a garden shed of some size, complete with corrugated roof. In time it developed a lean, and eventually supported itself against the brick wall. After a further period it became very dilapidated and we had full permission one weekend to demolish it. We did the job thoroughly and completely. It was a Sunday morning. The time chosen was perhaps a little unfortunate. In a similar but larger corrugated building only a few yards away our attention was drawn to the fact that a religious service was being held.

A Matter of Choice

When I reflect back to this period of our lives again, it gives me, as I am sure It gives my colleagues, a greater realisation of the amount of sound that penetrated into Charles Hendtlass’ study in the name of music. One thing that was very rarely lacking at Underwood was the provision of music in one form or another from the classics to jazz. If we consider for a moment, in the room on one side of his study was a radio which was on at almost every opportunity, on the other side a piano which was often pounded by ambitious, if unlearned, musical fingers; and it was highly probably that a gramophone was being played upstairs.

The first radio set we had was brought down by John Price who kindly put it in the outer study for the use of us all. Jerrold Weinstein later brought down a smaller set which was fitted up in the dining room at times. These were greatly appreciated, particularly at weekends and in the winter, and many plays and other programmes were listened to regularly. A particular favourite of the period I remember was the thriller series entitled “Appointment with Fear”. After the supper meal there would be a rush to obtain the best places near the wireless and fire, and concessions were granted to stay up for these late programmes and plays of special interest.

Naturally the news bulletins always had attentive listeners, particularly after the European invasion, and Winston Churchill’s masterly speeches of our time commended full attention with the whole hostel sitting around on chairs and on the floor. When John Price and Jerrold Weinstein left, John Clarridge brought down a set for our use, and later on John Garcia added a further one.

Gramophone music was provided by Joshua Mynk, and in later days by Roger Batey and John Krieger, and many record sessions were held, some on the lawn in fine weather. These were mainly concentrated on the dance and swing music of the day, and such outstanding names as Glenn Miller, Duke Ellington and the Dorsey Brothers.

Although popular music certainly had its followers there were probably as many devotees to the classical type, and there was for instance, a particularly interesting debate held one Sunday evening when Roger Batey defended jazz and Peter Norman the classics, both sides well illustrated with records. Apart from our own poundings, when the piano in the dining room was in the fully accomplished hands of Charles Hendtlass, our classical musical learning was enlarged and enriched and much enjoyment was provided, even if such items as “In the Hall of the Mountain King” were repetitively played, often to the accompaniment of the clatter of china and cutlery.

Keith Donohue also played often and his duets with Charles Hendtlass gave particularly entertaining moments. An Old Violin, Clair de Lune, Beethoven’s seventh symphony and perhaps Chattanooga Choo Choo. A grand pot–pourri!

Gay Spirits

As the end of a term was approaching, with the thought of holidays ahead, there was always a mood of added gaiety, merriment and general high spirits, which reached a crescendo by the last night. The packing of luggage at least a week prior to the term end was among the first real signs of impending holidays. Labels and string were borrowed and hurriedly fixed to cases and trunks which accumulated outside the front door awaiting collection. Inside, the bedroom walls which hitherto had been bedecked with coats, caps, uniforms, and meretricious ties, were horribly bare. The amount of set school preparation work decreased, and preparation periods were therefore not kept fixedly at these times, but a quiet room was always maintained. In the yard outside, or in the garage, bicycles were getting greater attention as many of us cycled the thirty miles back to London. On the last evening of term itself Mrs Hendtlass always prepared an extra special meal for us, at the end of which a suitable word was said to those leaving Underwood and this was accompanied by a leaving gift from the hostel. The meal was usually followed by games or competitions held on the lawn on lighter evenings whilst winter confined activities indoors.

The type of competition often organised by Charles Hendtlass, and which proved very popular, was a form of treasure hunt. There was one particular mammoth hunt which stands out above the others. The hostel was divided into pairs – my partner was Maurice Swaine – and we were given a long list of articles which were to be obtained from outside the hostel grounds. We had two and a half hours available and some of the items to be sought out included a fried chip, a platform ticket, a bus ticket whose number was divisible by eleven, a blonde hair, a piece of paper stamped with a bus conductors’ machine, the footprint and signature of the man on level crossing duty, a perfectly round stone, a log, a set of false teeth, and a smear of lipstick. A request for the last item caused at least one of our number some lengthy explaining, and the false teeth really proved the hardest to obtain. Jerrold Weinstein and Leo Melzer were the only pair to obtain them – from Timms’ garage! Their enterprise earned them the first prize and our own efforts brought Maurice Swaine and I the second prize.

On these occasions going to bed became a rather prolonged affair. Holiday spirits took command and pillow fight raids between bedrooms would follow. Even Charles Hendtlass would often unwittingly get caught up in the melee.

One such raid was one planned by the big bedroom for the early hours of the morning, and following the summons of an alarm clock some very tired members proceeded to the end room. Although the element of surprise was lost, as one of their members was awake, the raid was marked up as a success.

The Christmas terms had an understandable individuality of their own. There was the added festive atmosphere and

events were confined indoors. Added to the special end of term meal the Christmas pudding was always brought in, in a flaming condition, to a momentarily darkened room, and then eagerly devoured not only for taste, but for financial content. After the meal it became the custom for each bedroom to enact a short play or provide some other similar entertainment, and extra group sketches were also contributed. Some participants would rehearse for this for some weeks previously, whilst for others one or two rehearsals would suffice and on the night would prove to be quite sufficient.

In the gaily decorated dining room a large sheet would be strung across the room and periodically moved across, acting as a curtain. Between the actual plays or sketches, whilst others prepared, Mrs Hendtlass would pass food and sweets round and Charles Hendtlass played the piano for community singing.

Of the plays themselves, even when seen in retrospect, it can be said that some creditable performances were given. In 1942 for instance, a presentation by the big bedroom of the mystery ‘The Monkeys Paw’ was given, whilst a year later, with the room in semi-darkness, a dramatic performance of ‘The Mystery of Y’ was presented.

A tremendous amount of fun was obtained from all these shows. In the last named for instance, we had Maurice Swaine who took the part of a corpse, and who shook with mirth throughout; and in an earlier year Leo Melzer had us all in fits of laughter with his female impersonation. John Garcia on another occasion gave a splendid performance dressed as an American corporal, and probably one of the most effectively realistic, but incredibly simple pieces of acting came from Monty Foster, who in one sketch made quite a number of exits, by going off behind the piano, but as if descending some stairs. Items of a variety nature were often included, and a version of the popular radio programme of the time, ITMA, was put on by the end bedroom and with Monty Foster, Michael Watts, Torben Nordal and Roy and Guy Jones. It came over very well.

In 1944 I discussed the idea of putting on a variety type show with John Corcoran, and calling it the Flanagan and Allen guest show. This was ambitious and raised many difficulties, including the provision of any musical accompaniment, but we did manage some rehearsals. On the afternoon of the last day of term Monty Foster reviewed the evening programme, and there was already a full schedule, and with room plays taking priority, ours had to be deleted. By the evening however, ours was reinstated again. I duly record and acknowledge the invaluable assistance given by John Corcoran, and in particular for carrying on at one awkward moment, when in the final scene I took longer than anticipated to don evening dress, and he organised some community singing. He thereby did very much to obtain first prize for us that night!

Back in the Blitz

At this time, London was nearing the end of the blitz and other cities were becoming the target for quick, heavy bombing raids. The London blitz didn’t really affect us, as we were just outside the visual and audible sound of anything in the London area.

Now, however Midland cities were to become the targets and as at East Grinstead we would hear the continuous roar of bombers night after night, but we never had any local incidents. After a while these raids stopped and there was a quiet period for a time.

The enemy were to change their tactics and were developing fast fighter-bombers. These would be used for raids to be carried out in the quickest amount of time with the element of surprise. In 1941 the approaching winter brought with it terrible weather and this was to suit the enemy, when quick daylight raids started. These were ‘sneak’ raids when a handful of enemy planes would dive out of the low clouds on an appalling day, drop their missiles, and try to get away before the defences could get into any action. The first raids of this series were carried out on South Coast seaside towns.

Gradually, the enemy’s targets moved inwards from the coast, and one evening Reading was the target.

After afternoon school on a rainy day I went into Wokingham, and just after I arrived the air raid warning sounded. Thinking it best to make straightaway for Underwood I left there immediately. Just as I was leaving there were about six loud explosions which I knew were not far way. The centre of Reading was hit, unfortunately with quite a few casualties, and other bombs fell on Woodleigh, Reading's aerodrome. After this raid, we had other alerts, but there was no further close enemy activity.

Some considerable time later, I was to experience at close hand one of these fast, surprise sneak raids. This was when I was in Beckenham on school holiday, and it happened on 20th January 1943. There was a great contrast in the weather. Whereas previous raids had been carried out in dull, rainy conditions, this day was bright but cold, with hardly a cloud in the sky. The Germans were making hit and run raids to gain maximum surprise, and the main way they achieved this was to fly in at sea level to escape our radar detection which was virtually ineffective at this level.

I had been to the shops and as the siren had just sounded I was cycling home along Southend Road (between Park and Brackley roads) when, without any warning there was the loud sound of machine gun fire and a plane flew overhead at roof-top height. Instantly I recognised clearly the black crosses on the wings and identified it as a Focke Wulf 190 fighter bomber. A matter of seconds later, a second enemy aircraft roared overhead. I admit to being scared and hid underneath a stationary laundry lorry waiting for any further planes, but none came. So I cycled home as quickly as I could.

I had noticed earlier that all the barrage balloons were grounded, and as I turned down Brackley road I could see a big black cloud of smoke pouring out where a grounded balloon had been machine gunned. In the afternoon I went round to the balloon site in very quick time. This raid was when the ‘school on the hill was bombed in Lewisham.’

It turned out to be Sandhurst School in Catford, when 38 children and 6 teachers had been killed.

At the Alert

Back in Underwood, it is an opportune moment to remind ourselves of the reasons for our being in the somewhat remote, but delightful part of Berkshire County, and to see what general effect the war had on our lives. Once the immediate problems of the evacuation had been resolved the rhythm of scholastic life settled down to a steadier tempo, although in a war of such magnitude there was always uncertainty. The evacuation took us out of an assumed target area to a place of comparative safety in the country, and as far as enemy air activity was concerned, it was fortunately mainly isolated.

I understand that in the early days of “Underwood”, the sounding of the siren produced a certain amount of apprehension and at night all trooped downstairs while tea was made, books read and cards played. This soon clearly became unnecessary although, ironically when this ceased to be the practice, a few stray small bombs were dropped in the area one night, the only ones to fall locally throughout the war. There was however plenty of aircraft activity, and it was particularly marked by enemy planes when they crossed the area to raid midland towns and cities. The roar and throbbing of aircraft engines was heard while the planes travelled northwards, returning a short while later, and this sequence was to be reversed later in the war when our own aircraft went on their nightly bombing missions. Air activity was at its greatest on the morning of the European invasion and the noise and sight of the tremendous air armada passing over will long be remembered.

We assisted in one small way with civil defence by carrying out duties at the Brackwell Report centre. This comprised two small rooms at the back of the council offices, and two of us assisted on three occasions a week, the hours of duty being from nine o’clock on Monday and Friday evenings until the following morning with an extra shift on Fridays from five to nine o’clock in the evening.

About twelve senior members of “Underwood” participated on a rota basis.

Except for being confined to the rooms in question, which became unbearably hot on occasions as the black-out and gas proofing excluded virtually all ventilation, there was very little in the way of hardship or disturbed nights. The main duty involved was to advise outlying warden posts, outside the audible range of the sirens, of the times when alerts were in progress, and also to record other activity in an ‘incidents’ book; happily this was very rare. On the sunrise that ARP duty imposed a certain amount of strain we were allowed to miss school periods for half of the following day. When the number of alerts diminished this was amended to apply only when there had been an air raid warning.

During the period that followed there were sporadic raids, but in the summer of 1944 London was in for a very rude awakening; when a new weapon was launched against this country from France, the pilotless aircraft or flying bomb.

The first bomb was launched on 12th June 1944 and they were then sent over day and night for ten weeks. As the allied forces over-ran the launching area, so a second phase began when Heinkel III bombers were adapted to carry flying bombs and these were then launched from the air. This began on 16th September when these bombs were first launched.

On one of the Friday early evening periods I was at the Report centre when a particularly loud aircraft drew my attention and I went outside to see it. I noticed that it appeared to be on fire with flames pouring from it, and it was not flying very high. It was travelling towards Binfield and as it was about to disappear from sight, the engine stopped. I went and related this to my companion John Singleton who was full of skepticism. Ten minutes later the Report Centre at Bagshot telephoned to warn us that a flying bomb was approaching! Subsequently, I understand this caused considerable excitement at the hostel, and it finally crashed harmlessly in open country. This was fortunately a stray and we were saved the horror that these new weapons brought.

There was however another occasion later when I cycled to Windsor one Sunday afternoon with Bryan Cross, and as we made our way so the weather deteriorated. When we reached the outskirts of the town there was suddenly a violent explosion and within seconds smoke was rising a very short distance away. There was no alert in progress, and in the appalling weather we had heard nothing. Rescue vehicles and ambulances were very soon in evidence and another V1 weapon had unleashed its destructive powers.

There were other enemy incidents, but generally of an isolated nature. For instance, on an equally wet afternoon as the Windsor episode, I was in Wokingham when the siren sounded. The wailing had hardly ceased when there were several distinct explosions, and then it was all over. The target had been Reading which received direct hits in the town centre during a ‘hit and run’ type of raid.

The heavy raids on London did not directly affect us in any way, but when the blitz was renewed for a period in 1944, the raided area covered a much larger area than previously, and on what proved to be the last night of these attacks, found us on the perimeter with much activity, with fortunately little danger. Prior to this a number of gun batteries had been sited in the environment, and although not at close quarters, they added a distinctive sound to the general roar. Searchlights were on in many numbers probing crazily in the sky, which was soon transformed into a stark brilliance by the many flares which were dropped.

Apart from air activity, which had a grandeur of its own, other war reminders were provided by army convoys which consistently passed through the district, and also by an ammunition store which was created extensively in Easthampstead Park, and later extended in Nissen huts to other roads outside the park area.

With our own preoccupations of this time, it is most probable that we did not realise fully sometimes the effect and significance of happenings in other places. We do therefore give grateful thanks that the war’s impact was no greater for us.

Out and About

A necessity of the first order at Binfield was a bicycle, and even temporary embarrassments like punctures and broken chains could leave us with a great sense of immobility, as if we had been deprived of one of our driving forces.

The acquisition of a cycle however did give us the opportunity of visiting places in the neighbourhood, and cycle rides, particularly at weekends, were very popular. There was an ‘out’ book at the hostel in which we entered proposal destinations and expected time of return. The more leisurely amongst us were content to go for only short distances, perhaps pedaling for a few yards, and then free-wheeling as far again, and so repeating the process. For others the pace was fast, probably covering the same distance in half the time.

The considerable air activity previously referred to had stimulated great interest in aircraft identification, and consequently in any visits to neighbouring aerodromes. Although of course there were strict security precautions, they did not generally prevent us from viewing at fairly close quarters without actually stopping. Geographically the nearest aerodrome was at Woodley, between Wokingham and Reading, but there was very little apparent activity here and it was difficult to see very much. Another aerodrome where we fared much better was at White Waltham, outside Maidenhead, where we saw many different and up to date operational aeroplanes. Visits here were made frequently and a variety of different types of aircraft provided continual interest, from trainers to those not officially released from the secret list. John Price, John Pitt, Ben Nordel, Michael Watts and John Claridge were regular visitors here. The aerodromes at Farnborough and Slough were other places included, but ground observation was difficult, and visits here were infrequent.

The nearest town of any size was the county town of Reading, twelve miles distant, and this was a popular choice at weekends for shopping or tea, with an added attraction being the league football matches played at Elin Park. I recall going with John Singleton, Eddie Veronique, John Dunwoody and Adolfo and Manuel Bulla amongst others, to see many attractive games. The added draw here was the number of well-known names who guested for Reading during the war whilst serving in the armed forces and being stationed in the area.

Nearer to Binfield we had the opportunity to partake in two sports not directly organised by the school, swimming and tennis. There was a particularly picturesque swimming pool at Wokingham, where all Paulines had concessionary terms. Many of us used the pool, although at times it became very crowded. Towards the end a natural pool was discovered in Binfield in the grounds of a local brick-works, and this was used quite often.

With tennis we were able to play at various courts nearby. In 1943, for instance, two courts near Bracknell were used frequently by Irving Hartstein, Joshua Mynk, and Jerrold Weinstein but eventually this was stopped when the Air Force claimed possession. Alternative courts in Binfield, previously little used, were found and we played on them provided that we kept the courts regularly swept and weeded. John Singleton, Norman Kirke, John Claridge, Michael Mather and John Garcia were regular players here.

In winter months, with most outdoor activities curtailed, the cinema became popular for an evening out. There was the Regal at Bracknell, and the Ritz (and Savoy?) at Wokingham, and with a mid-week change of programmes, weekday evening visits were allowed provided that those who went rose early the next day to carry out the preparation period missed. As would be expected, cinema visits were prohibited on Sundays, unless the film was exceptional.

I hesitate to think of the mileage covered by each of us on our cycles during our stay but it was no doubt a formidable figure. The opportunity to get about was an added advantage over our town habitat, and I am also sure the resultant alfresco type life we led was by its nature of great benefit to health.

The Final Encounters

Before returning home for the summer holidays I was to experience another encounter with a flying bomb. I cycled to Windsor one afternoon weekend with a friend on a dull day with low clouds but hardly any wind. We were just entering the outskirts of Windsor when we heard the distant sound of an aircraft, but with low clouds nothing could be seen. I was just trying to identify the sound when it abruptly stopped. There was silence and we rode on quickly and I was just a little scared. Suddenly there was a heavy explosion very close to us, and we felt the ground vibrate. Before long we saw a large cloud of black smoke caused by the bomb, and we saw that a small factory nearby had been hit with damage to surrounding houses. We soon returned to Binfield.

At the end of the school term, being keen on cycling, I cycled the forty-mile journey home. It was a glorious day for cycling and the journey went well until I reached Kingston. I was just leaving there when the siren sounded, and within a few minutes I saw people hurrying past and the familiar roar of a bomb was heard. I immediately dismounted and took shelter in the subway of Raynes Park Station. Someone shouted for us all to lie low, as a bomb’s engine had just cut out, and seconds later there was a loud explosion with considerable vibration. We heard a second bomb come over and then soon afterwards the ‘all clear’ sounded and I continued the journey.

All the way home there was a scene of destruction all over the place. Houses, shops and churches had been badly damaged, windows had been smashed everywhere, and people were repairing their homes as best they could. I shall never forget entering Beckenham on this ride. On 2nd of July 1944 a flying bomb had fallen in the built-up shopping area of Albermarle Road at Beckenham Junction, close to the Railway Hotel which stood in the High Street facing Rectory Road. Boards and other materials were laid out all over the roads, being cut up to fill in some of the gaps. Three people had been killed with thirty injured and twelve shops, a garage and the hotel had been destroyed.

Only a couple of weeks later a second bomb fell at almost the same spot, close to the Parish church in Church Road. This was a short road parallel to Albermarle Road, joining the High Street to St. Georges Road, and now no longer exists. The church suffered severely, all the East and North side windows were blown out and the roof very badly damaged. After the war a number of plans for the re-development were considered, but eventually the area was left open and landscaped, and the opportunity was taken to re-align the end of Albermarle Road to line up with Rectory Road.

On the evening of 17th July the bus garage at Elmers End received a direct hit and widespread damage was caused. 18 people were killed, over 40 injured and in addition 27 double decker and 2 single decker buses were destroyed along with 10 ambulances. The garage, which stood on the corner of Beck Lane and Elmers End Road, was never rebuilt after the war and is now a residential area.

The above two incidents were two of the worst in Beckenham but the most tragic occurred at lunchtime on 2nd August when a flying bomb fell on a crowded British Restaurant in the main road at Clock House. 44 people were killed and several shops and 12 houses were destroyed. The shops were never re-built and apart from the new Clock House public house on the site, the area has been left largely undeveloped.

I stayed in Beckenham for about a week, which I found quite terrifying. In the evenings, the siren sounded and the flying bombs soon started coming over in twos and threes. For most of this week I spent much of the time in our Anderson Shelter in the back garden. I only entered the house for meals and didn’t dare to go far from the house. At nights I slept in the shelter but it was difficult to get to sleep. It wasn’t possible to see anything in the shelter but there was plenty to hear. After a week of this terror, quick arrangements were made and I left for Scotland. I travelled overnight, but didn’t get much sleep as the train was packed and there were many soldiers on the train lying wherever they could on floors and tables. In fact, when the guard came along later, to great cheers he was just carried over everyone.

Coastal Battles

I went to Leven and had a good holiday by the sea, where there were very few signs of war.All good things come to an end and after some weeks I returned to Beckenham and had a much better return journey. As the raids were still on, it was arranged that I should only stay one day in Beckenham and then go on to Deal to help in harvest work, and join my cousin Robert who was already there. There I was to experience another of the enemy’s weapons – the cross-channel guns.

The south and south-eastern coastal areas were restricted areas for about ten miles inland and it was necessary to have a permit to enter this zone. However, the farmers were appealing for extra help at harvest time and we were made very welcome. We stayed at a farm at Great Mongeham which was a small village a mile or so behind Deal.

When I arrived it was relatively quiet and flying bombs didn’t actually come overhead but about four miles further down the coast at Dover. Also, there hadn’t been any cross-channel shelling for a while, and I was told that was only occasional when a British convoy passed through the straits. The weather was very good, and when I could I visited Deal and walked along the front and it seemed amazing to see how close the enemy coast appeared to be. One evening, after one of our bomber forces had passed over; it seemed hard to believe that the terrific ack-ack barrage, a few miles out at sea, was being put up by the enemy.

The second week of my stay was to be rather different, as the Germans were moving their launching sites further up, as the British advanced, and correspondingly our defences were being moved.

Overnight a great number of heavy anti-aircraft guns appeared along the front in Deal, and in fields around us other batteries of heavy and light guns appeared. During the days, terrific barrages were put up overhead as these flaming missiles roared over and little farm work was done from then on. As we watched it appeared that the shells used to burst a good way behind the bomb, but by the time we saw the puff of smoke the bomb had already travelled a fair distance.

The last few days of my stay, was when there was a big allied push through France, and the cross-channel guns had their final fling.The last night in particular was a bad one. There was no warning whistling when the shells were coming; there was just a loud explosion and vibration when they hit the earth. The periods of shelling would last about two hours at a time, and while we were out for a stroll, a shell landed fairly close, and some farm buildings went up in smoke. The shells would generally land, four at a time, in quick succession every five minutes throughout the night until about 6:30 a.m. the next morning. When the shelling finished the flying bombs started again. So it was that I left for Beckenham, but in contrast to the shelling and bombing, I left behind one strange experience of complete quietness.

On one free afternoon I visited Margate after a difficult journey there. I walked down Northdown Road then down along the seafront, and it was extremely eerie. There was not a lot of bomb damage, but it was just that everywhere seemed to have closed down and been boarded up. At the most there were about six shops open, doing no trade, and there was hardly a person to be seen. I returned via Broadstairs which was very much the same.

A New Horror

Back in Beckenham, things had quietened down a bit as the damaged buildings were being cleaned up, but we were shortly to be subjected to a new horror.

This was the V2 or rocket. There was absolutely no warning, just a very loud explosion when they hit the earth. They were as tall as a large house, and sound waves radiating from the centre of the explosion could be heard for about 15 seconds after. I spent another term at school, and then returned home for the Christmas holidays.

The first rocket to fall in Beckenham fell close to our house, on 2nd January 1945 just after noon. I was alone in the house when there was a terrific crash, with severe vibration and some of our doors flew open forcing the locks. Fortunately it had fallen in a sports ground. The Midland Bank sports ground close to New Beckenham station.

Exactly a week later, at about the same time, on 9th January a second rocket fell, and coincidently this also fell on a sports ground close to the first, the Cyphers ground in Kings Hall Road.

Shortly after I went around to both scenes and saw large craters about twenty feet deep and forty feet wide.

In the midst of these two rocket incidents, another flying bomb was to hit Beckenham and it proved to be the last. At 10:30 p.m. on January 5th the siren had just sounded after I had gone to bed. Almost immediately I heard the familiar roar, as it passed over the house. No sooner had it passed than the engine cut out, followed by an explosion and a bright red flash.

The next day I saw that the High Street had been blasted, and the bomb had hit Christ Church on the corner of Fairfield Road and the High Street. This bomb, as with most of this final phase, had been launched from a Heinkel III over the sea. The last one to be launched was at the end of March.

After the war, when various facts and figures were made known, it was revealed that London and the south-east were subjected to most of the flying bombs. No less than 9,251 bombs were launched against this country, with 2,419 reaching London. With a large number of the bombs travelling over Kent, the county became known as Bomb Alley! Beckenham, along with other south-eastern suburbs, suffered very badly with 70 falling in the borough. Interestingly, after the campaign was over, it was revealed that in tests the bombs often fell short and that German agents had been given misleading information and the result was that many fell short, and this was one reason why Beckenham suffered badly.

The only towns in Kent that were not hit by a flying bomb were Chatham, Sheerness, Margate, Ramsgate, and Sandwich. The first rocket or V2 was launched against England on 8th September 1944 and the offensive continued until, like the flying bomb, the allied Forces over-ran the launching sites. The last rocket to fall was at Orpington on 27th March 1945.

Due to the nature of the Rocket offensive, the 1,115 which landed (and the distance they travelled) fell over a very wide area, 517 falling on London, with Beckenham having only 6.

Our Greatest Moments

The end of our war in Europe was a time for rejoicing, for thanksgiving, for jubilation and celebration. It provided the greatest and happiest moments at Underwood during our stay there.

We had awaited official news of the end of the European war for many days, and had listened intently to the various radio news bulletins. “Negotiations were proceeding” became an oft-repeated phrase. One evening on 7th of May 1945 a small group of boys listening to the wireless heard the announcement that the morrow would officially be celebrated as VE day, the Victory in Europe day. The result of this announcement was electrifying. In seconds the news had spread throughout the hostel and the majority took up the mood that the announcement had created, rushing out across the lawn, until nearly the entire hostel had assembled in the road outside. It appeared that the “Jack of Newbury” would be the objective as the hostel moved en masse down the road singing joyously. John Singleton, Maurice Swaine and I walked on behind the main crowd and already flags were appearing at windows and the good news was being exchanged. This march through Binfield was soon halted and we all returned to the house as Charles Hendtlass had sent word that he did not wish us to become too scattered; so permission was obtained instead to visit the Roebuck next door.

So it was we drank, smoked and talked together and with the many villagers who found their way into our company. Shortly after this we returned again to the house where Mrs. Hendtlass had prepared a short but very appetising meal.

It was now beginning to get dark and after the meal preparations were made for a large bonfire on the lawn, with the more enthusiastic amongst us carrying large logs and other timber to ensure success. The fire was soon lit, which was of a very considerable size, and provided a blaze of marked brilliance. The villagers were making their way into our grounds, and as the fire grew in intensity there must have been nearly a hundred people there.

With the sparks flying, a ring was formed around the fire with everyone singing and dancing merrily, while Mrs. Hendtlass passed a tin of biscuits around the assembly. This merry throng continued for a long time but eventually broke up and there was a period of anti-climax.

Marty Foster and Maurice Swaine tried hard to start some dancing but the problem was to find a source of music. Eventually the piano was moved to the dining room window and Charles Hendtlass played, with everyone joining in the singing. The attempt to start dancing was not entirely defeated as late-night dance music from the radio allowed a few couples to dance in the restricted space of the inner study.

At about this time it started to rain and this undoubtedly caused the crowds to scatter. Most of the villagers now left and we went indoors for supper and to drink a victory toast. Having made sure that all outsiders had departed we adjourned to the bedrooms whilst outside a heavy thunderstorm broke out. The evening of enjoyment was coming to an end as Charles Hendtlass came round to see that that the hostel was returning to normality.

I watched from the bedroom window the effects of the storm. The lightning was very vivid and thunder reverberated around the house. The bonfire was still burning fiercely and the lawn around it was turned into a series of small ponds while the drenching rain played tricks with the fire.

Uncertain Departure

With the war now over, a period of adjustment was necessary before there could be any return to normality. This meant, as far as the school was concerned, much work to be done to the buildings at Hammersmith before any return to London.

Following the recalling of events at Underwood in celebration of the victory in Europe, we now come to the final term at the hostel. It was however one which proved to be both difficult and disappointing. Difficult, because illness broke out on a large scale shortly after half-term, and disappointing because a number of planned ideas to mark the end of our stay in Binfield did not come to fruition. Also, there was a prolonged period of uncertainty because in the event it was not until virtually the last day of term that it was definitely announced that the school would be returning to London for the following term.

Mrs. Hendtlass suggested that as a hostel we might put on a play in the village, but this idea was not generally adopted, and as an alternative the previous idea of room plays for the end of term was to go forward. In addition, I had the idea of putting on an extra item with the theme “Goodbye Underwood.” This idea was developed with John Corcoran and Ian Clark. Michael Mather, Monty Foster and Brian Powell were to join us in the presentation. The first setback with this occurred after half term when Michael Mather caught mumps, followed shortly by Ian Clark. Brian Powell unfortunately followed those confined to bed, and although John Dunwoody and Bryan Cross helped to fill the depleted ranks, with the end of term examinations near at hand, and insufficient time for rehearsals, the idea had to be abandoned. Apart from John Corcoran I was particularly indebted to Monty Foster for his sterling aid for getting programmes printed, and to John Dunwoody for his very considerable encouragement.

On the last night itself we were glad to welcome back several of our ‘old boys’ including Jerrold Weinstein, Leo Melzer, Maunel Buylla, Eddie Veronique and Peter Norman. In the early evening a small treasure hunt was arranged by Charles Hendtlass with clues given out in jumbled fashion and then followed by games and races on the lawn. The difficulties of the past term were still reflected on this last night. The mumps which had dogged some of our members through the latter part of the term was still with us.

John Claridge and Brian Powell had the great misfortune through necessity to be isolated in the inner study throughout this last evening. To add to the confusion during the evening, all the lights failed for a while. Later in the evening however we all settled down for the usual very enjoyable meal and after this, with our old friends present, Charles Hendtlass made a short speech when he summarised some of the greater moments at Underwood.

Following this, Monty Foster on behalf of all Underwood, presented Charles and Mrs. Hendtlass with a silver flower vase and fruit stand in appreciation for all they had both done for us throughout our Binfield sojourn, and Charles Hendtlass gave his sincere and grateful thanks. A present was next given to those of us who were actually leaving school that term, and was in the form of book tokens from Charles Hendtlass and in the form of books on their favourite subjects from Monty Foster on behalf our colleagues. Three of us left that term, John Singleton, Maurice Swaine and myself. I was truly delighted to receive two books on photography, and a third was purchased with the token. Autographed by all of these present, they are still particularly treasured. After the meal the process of getting to bed became a very prolonged affair, and further food and drink was partaken in the bedrooms.

The final morning of term dawned and most of us were up at an early hour and busy with last minute packing and clearing up. After breakfast we all made our way up to the mansion at Easthampstead Park to attend the last short school service.

As we assembled in Hall, there was a particular atmosphere prevailing, identified only with occasions of special significance. We were in greater numbers than normal, for the end of term was virtually the only time when all forms were at Easthampstead Park. On all other mornings some forms would start the morning at the Wellington College science laboratories in Crowthorne.

This sense of occasion grew and lasted throughout the short service. Alan Cook took up his position at the piano and other masters then came in to the Hall. The second bell was rung and the High Master entered followed by the head boy, Gerald Everett, who had stayed with us at Underwood for a short while. The hymn chosen for this final morning was sung with tremendous enthusiasm and slow precise determination.

“All people that on earth do dwell Sing to the Lord with cheerful voice

Him serve with fear, his praise forth tell Come ye before him, and rejoice”

The Bible passage read by the High Master was from the first epistle of Paul to the Corinthians and I recall thinking at the time, the relevance of one particular passage now that we were moving on. “When I was a child, I thought as a child; but when I became a man, I put away childish things.”

A brief speech was given by Walter Oakeshott who confirmed that it was only definitely known that very morning we would be returning to London the next term, and then thanked us all for our co-operation during these hazardous times. The service concluded and we quietly made our way out, to return home for the holidays. The doors of Underwood had now closed behind us and we would not be returning. It was 27th July 1945.

Fellowship

An era had passed for us and we would now go our separate ways. Memories we had though, and in an essay such as this it is only possible to recall a few of our occasions together, and there are many such items which unavoidably have to be omitted.

There was for instance, the Underwood Debating Society with John Garcia as President, debating for example ‘Modern films do more harm than good’ and later ‘Subjective Idealism’; the frequency of Timm’s garage to deal with all manner of cycle repairs, especially punctures; our patronage of Popeswood Post Office and other village shops; the occasion on a summer’s night when one of our number spent the night in the garden for a wager; the application by Charles Hendtlass from time to time of necessary punishments, on one noteworthy occasion being the result of mistaken identity in the dark (or was it?); these and many more.

Many happy memories. But is this all? I do not think so. For we were living together as a large united family, and from that sharing, communication, companionship, call it what you will, grew a family spirit which far outlived our actual stay in Binfield. It is still with us. As an example, the marriage of Charles Hendtlass showed without doubt how this spirit had been completely sustained. Eighteen years had passed since our dispersal from Binfield, and yet no less than nearly thirty pounds was contributed to Charles and Kathleen in the name of Underwood.

There are also times of sadness which all families have to bear, but in a family such as this, the hardship and sense of loss somehow seem just that easier to carry. Nevertheless, it is sad to have to record that of the fifty-eight who passed through Underwood, six were to meet a most untimely death. Even during our stay, Roger Batey did not survive an operation and died tragically in the summer of 1944. In the early years following the war, Leonard Shrimpton, John Pierce, John Claridge, John Price and Michael Mather on a military service in Malaya. Each one in their own way, made a valuable contribution to the success of the hostel, and they will long be remembered and sadly missed by us all. For me, at any rate, such happenings only strengthen faith and belief in Christian teaching.

While I was making final notes for this chapter I also learned that Mrs. Hendtlass had died in her seventies. To her must go a very considerable share of the credit for the success of Underwood, and particularly for taking on the immense task of running the kitchen, almost singlehanded, and for which all of us will always be grateful.

In any final reckoning, the pointer to the success of the hostel must surely be the teamwork which existed, and which was headed by the industrious and zealous leadership of Charles Hendtlass. It is also perhaps significant to note in passing that discipline was maintained by instituting only such rules that were clearly necessary. Charles, together with Mrs. Hendtlass, worked tremendously hard for the success of Underwood.

Since the end of the war there have been three reunions of past members, significant itself of the continued fellowship, and the only hostel to continue meeting in this way. The first of these reunions was held as a dinner in July 1948 at the Restaurant Desgourmets in London. To my great chagrin I was prevented at the very last moment from attending, but it was declared a great success and Geoffrey Samuel penned the following for the “Pauline.”

“the ‘Underwood’ reunion was held on Saturday July 24th 1948 at the Restaurant Desgourmets in Lisle Street, W1. Before the Commencement of the meal, W.N.M. Foster, on behalf of the old “Underwoodians”, presented flowers and a spray to Mrs. Hendtlass as a small token of appreciation of her work during the war years. And, indeed, every individual joined him in recognising the debt owed to her for the remarkable and inspired way in which she managed those affairs in the hostel which were entrusted to her care. After the excellent food and drink had been enjoyed, friends long since parted, enquired how they had spent the intervening years.

Those present truly represented Underwood from 1940-1945, the ages varying by as much as ten years. The majority of those present had served or were serving with H.M Forces, and perhaps the only sad moments in a very agreeable evening were caused by the realisation of how many old friends were absent, either through service duties or other natural reasons.

Eventually the evening drew to a close, but not before Mr. Hendtlass had passed a sincere vote of thanks to A.W Ramage (unfortunately prevented from coming) for making all the arrangements, and had expressed the hope that it would not be many months before we met again. With this happy thought to console us as we left, the party trickled out of the restaurant, still reminiscing about days long since passed.”

The second reunion was held at Underwood itself in July 1950. The owner at the time had kindly given permission for a picnic to be held on the lawn, but unfortunately the day turned out to be very wet, and we had to confine ourselves to the nearest shelter available, a room at the “Roebuck” next door. The following account subsequently appeared in the “Pauline.”